Persistent Objects and Caché SQL

A key feature in Caché is its combination of object technology and SQL. You can use the most convenient access mode for any given scenario. This chapter describes how Caché provides this feature and gives an overview of your options for working with stored data. It discusses the following topics:

Introduction

Caché provides what is sometimes called an object database: a database combined with an object-oriented programming language. As a result, you can write flexible code that does all of the following:

-

Perform a bulk insert of data via SQL.

-

Open an object, modify it, and save it, thus changing the data in one or more tables without using SQL.

-

Create and save new objects, adding rows to one or more tables without using SQL.

-

Use SQL to retrieve values from a record that matches your given criteria, rather than iterating through a large set of objects.

-

Delete an object, removing records from one or more tables without using SQL.

That is, you can choose the access mode that suits your needs at any given time.

Internally, all access is done via direct global access, and you can access your data that way as well when appropriate. (If you have a class definition, it is not recommended to use direct global access to make changes to the data.)

Caché SQL

Caché provides an implementation of SQL, known as Caché SQL.

Caché SQL supports the complete entry-level SQL-92 standard with a few exceptions and several special extensions. Caché SQL also supports indices, triggers, BLOBs, and stored procedures (these are typical RDBMS features but are not part of the SQL-92 standard). For a complete list, see Using Caché SQL.

Where You Can Use Caché SQL

You can use Caché SQL within routines and within methods. To use SQL in these contexts, you can use either or both of the following tools:

-

Embedded SQL, as in the following example:

&sql(SELECT COUNT(*) INTO :myvar FROM Sample.Person) Write myvarYou can use embedded SQL in ObjectScript routines and in methods written in ObjectScript.

-

Dynamic SQL (the %SQL.StatementOpens in a new tab and %SQL.StatementResultOpens in a new tab classes), as in the following example:

SET myquery = "SELECT TOP 5 Name,DOB FROM Sample.Person" SET tStatement = ##class(%SQL.Statement).%New() SET tStatus = tStatement.%Prepare(myquery) SET rset = tStatement.%Execute() //now use proprties of rset objectYou can use dynamic SQL in any context.

Also, you can execute Caché SQL directly within the SQL Shell (in the Terminal) and in the Management Portal. Each of these includes an option to view the query plan, which can help you identify ways to make a query more efficient.

Object Extensions to SQL

To make it easier to use SQL within object applications, Caché includes a number of object extensions to SQL.

One of the most interesting of these extensions is ability to follow object references using the reference (“–>”) operator. For example, suppose you have a Vendor class that refers to two other classes: Contact and Region. You can refer to properties of the related classes using the reference operator:

SELECT ID,Name,ContactInfo->Name

FROM Vendor

WHERE Vendor->Region->Name = 'Antarctica'Of course, you can also express the same query using SQL JOIN syntax. The advantage of the reference operator syntax is that it is succinct and easy to understand at a glance.

Special Options for Persistent Classes

In Caché, all persistent classes extend %Library.PersistentOpens in a new tab (also referred to as %PersistentOpens in a new tab). This class provides much of the framework for the object-SQL correspondence in Caché. Within persistent classes, you have options like the following:

-

Methods to open, save, and delete objects.

When you open a persistent object, you specify the degree of concurrency locking, because a persistent object could potentially be used by multiple users or multiple processes.

When you open an object instance and you refer to an object-valued property, the system automatically opens that object as well. This process is referred to as swizzling (also known as lazy loading). Then you can work with that object as well. For example:

Set person=##class(Sample.Person).%OpenId(10) Set person.Name="Andrew Park" Set person.Address.City="Birmingham" Do person.%Save()Similarly, when you save an object, the system automatically saves all its object-valued properties as well; this is known as a deep save. There is an option to perform a shallow save instead.

-

Default query (the Extent query) that is an SQL result set that contains the data for the objects of this class.

In this class (or in other classes), you can define additional queries; see “Class Queries,” earlier in this book.

-

Ability to define relationships between classes that are projected to SQL as foreign keys.

A relationship is a special type of object-valued property that defines how two or more object instances are associated with each other. Every relationship is two-sided: for every relationship definition, there is a corresponding inverse relationship that defines the other side. Caché automatically enforces referential integrity of the data, and any operation on one side is immediately visible on the other side. Relationships automatically manage their in-memory and on-disk behavior. They also provide superior scaling and concurrency over object collections (see “Collection Classes” in the previous chapter).

-

Ability to define foreign keys. In practice, you add foreign keys to add referential integrity constraints to an existing application. For a new application, it is simpler to define relationships instead.

-

Ability to define indices in these classes.

Indices provide a mechanism for optimizing searches across the instances of a persistent class; they define a specific sorted subset of commonly requested data associated with a class. They are very helpful in reducing overhead for performance-critical searches.

Indices can be sorted on one or more properties belonging to their class. This allows you a great deal of specific control of the order in which results are returned.

In addition, indices can store additional data that is frequently requested by queries based on the sorted properties. By including additional data as part of an index, you can greatly enhance the performance of the query that uses the index; when the query uses the index to generate its result set, it can do so without accessing the main data storage facility.

-

Ability to define triggers in these classes to control what occurs when rows are inserted, modified, or deleted.

-

Ability to project methods and class queries as SQL stored procedures.

-

Ability to fine-tune the projection to SQL (for example, specifying the table and column names as seen in SQL queries).

-

Ability to fine-tune the structure of the globals that store the data for the objects.

SQL Projection of Persistent Classes

For any persistent class, each instance of the class is available as a row in a table that you can query and manipulate via SQL. To demonstrate this, this section uses the Management Portal and the Terminal, which are introduced later in this book.

Demonstration of the Object-SQL Projection

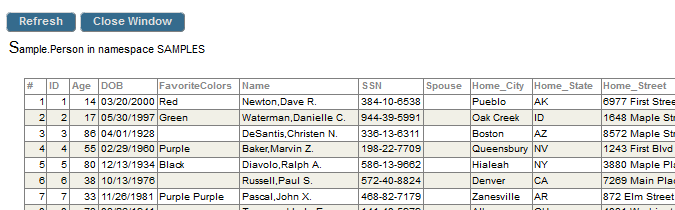

Consider the Sample.PersonOpens in a new tab class in SAMPLES. If we use the Management Portal to display the contents of the table that corresponds to this class, we see something like the following:

(This is not the same data that you see, because this sample is repopulated at each release.) Note the following points:

-

The values shown here are the display values, not the logical values as stored on disk.

-

The first column (#) is the row number in this displayed page.

-

The second column (ID) is the unique identifier for a row in this table; this is the identifier to use when opening objects of this class. (In this class, these identifiers are integers, but that is not always true.)

These numbers happen to be the same in this case because this table is freshly populated each time the SAMPLES database is built. In a real application, it is possible that some records have been deleted, so that there are gaps in the ID values and these values do not match the row numbers.

In the Terminal, we can use a series of commands to look at the first person:

SAMPLES>set person=##class(Sample.Person).%OpenId(1)

SAMPLES>write person.Name

Van De Griek,Charlotte M.

SAMPLES>write person.FavoriteColors.Count()

1

SAMPLES>write person.FavoriteColors.GetAt(1)

Red

SAMPLES>write person.SSN

571-15-2479

These are the same values that we see via SQL.

Basics of the Object-SQL Projection

Because inheritance is not part of the relational model, the class compiler projects a “flattened” representation of a persistent class as a relational table. The following table lists how some of the various object elements are projected to SQL:

| Object Concept | SQL Concept |

|---|---|

| Package | Schema |

| Class | Table |

| Data type property | Field |

| Embedded object | Set of fields |

| List property | List field |

| Array property | Child table |

| Stream property | BLOB |

| Index | Index |

| Class method marked as stored procedure | Stored procedure |

The projected table contains all the appropriate fields for the class, including those that are inherited.

Classes and Extents

Caché uses an unconventional and powerful interpretation of the object-table mapping.

All the stored instances of a persistent class compose what is known as the extent of the class, and an instance belongs to the extent of each class of which it is an instance. Therefore:

-

If the persistent class Person has the subclass Student, the Person extent includes all instances of Person and all instances of Student.

-

For any given instance of class Student, that instance is included in the Person extent and in the Student extent.

Indices automatically span the entire extent of the class in which they are defined. The indices defined in Person contain both Person instances and Student instances. Indices defined in the Student extent contain only Student instances.

The subclass can define additional properties not defined in its superclass. These are available in the extent of the subclass, but not in the extent of the superclass. For example, the Student extent might include the FacultyAdvisor field, which is not included in the Person extent.

The preceding points mean that it is comparatively easy in Caché to write a query that retrieves all records of the same type. For example, if you want to count people of all types, you can run a query against the Person table. If you want to count only students, run the same query against the Student table. In contrast, with other object databases, to count people of all types, it would be necessary to write a more complex query that combined the tables, and it would be necessary to update this query whenever another subclass was added.

Object IDs

Each object has a unique ID within each extent to which it belongs. In most cases, you use this ID to work with the object. This ID is the argument to the following commonly used methods of the %PersistentOpens in a new tab class:

-

%DeleteId()

-

%ExistsId()

-

%OpenId()

The class has other methods that use the ID, as well.

How an ID Is Determined

Caché assigns the ID value when you first save an object. The assignment is permanent; you cannot change the ID for an object. Objects are not assigned new IDs when other objects are deleted or changed.

Any ID is unique within its extent.

The ID for an object is determined as follows:

-

For most classes, by default, IDs are integers that are assigned sequentially as objects of that class are saved.

-

For a class that is used as the child in a parent-child relationship, the ID is formed as follows:

parentID||childIDWhere parentID is the ID of the parent object and childID is the ID that the child object would receive if it were not being used in a parent-child relationship. Example:

104||3This ID is the third child that has been saved, and its parent has the ID 104 in its own extent.

-

If the class has an index of type IdKey and the index is on a specific property, then that property value is used as the ID.

SKU-447Also, the property value cannot be changed.

-

If the class has an index of type IdKey and that index is on multiple properties, then those property values are concatenated to form the ID. For example:

CATEGORY12||SUBCATEGORYAAlso, these property values cannot be changed.

Accessing an ID

To access the ID value of an object, you use the %Id() instance method that the object inherits from %PersistentOpens in a new tab.

In SQL, the ID value of an object is available as a pseudo-field called %Id. Note that when you browse tables in the Management Portal, the %Id pseudo-field is displayed with the caption ID:

Despite this caption, the name of the pseudo-field is %Id.

Storage

Each persistent class definition includes information that describes how the class properties are to be mapped to the globals in which they are actually stored. The class compiler generates this information for the class and updates it as you modify and recompile.

A Look at a Storage Definition

It can be useful to look at this information, and on rare occasions you might want to change some of the details (very carefully). For a persistent class, Studio displays something like the following as part of your class definition:

<Storage name="Default">

<Data name="PersonDefaultData"><Value name="1">

<Value>%%CLASSNAME</Value>

</Value>

<Value name="2">

<Value>Name</Value>

</Value>

<Value name="3">

<Value>SSN</Value>

</Value>

<Value name="4">

<Value>DOB</Value>

</Value>

...

</Storage>

Globals Used by a Persistent Class

The storage definition includes several elements that specify the globals in which the data is stored:

<DataLocation>^Sample.PersonD</DataLocation>

<IdLocation>^Sample.PersonD</IdLocation>

<IndexLocation>^Sample.PersonI</IndexLocation>

...

<StreamLocation>^Sample.PersonS</StreamLocation>

By default, with default storage:

-

The class data is stored in the data global for the class. Its name starts with the complete class name (including package name). A “D” is appended to the name. For example: Sample.PersonD

-

The index data is stored in the index global for the class. Its name starts with the class name and ends with an “I”. For example: Sample.PersonI

-

Any saved stream properties are stored in the stream global for the class. Its name starts with the class name and ends with an “S”. For example: Sample.PersonS

If the complete class name is long, the system automatically uses a hashed form of the class name instead. So when you view a storage definition, you might sometimes see global names like ^package1.pC347.VeryLongCla4F4AD. If you plan to work directly with the data global for a class for any reason, make sure to examine the storage definition so that you know the actual name of the global.

Informally, these globals are sometimes called the class globals, but this can be a misleading phrase. The class definitions are not stored in these globals.

For more information on how global names are determined, see “Globals” in Using Caché Objects.

Default Structure for a Stored Object

For a typical class, most data is contained in the data global, which includes nodes as follows:

| Node | Node Contents |

|---|---|

| ^full_class_name("id")

Where full_class_name is the complete class name including package, hashed if necessary to keep the length to 31 characters. Also, id is the object ID as described in “Object IDs.” |

List of the format returned by $ListBuild.

In this list, stored properties are listed in the order given by the name attribute of the <Value> element in the storage definition. By definition, transient properties are not stored. Stream properties are stored in the stream global for the class. |

For an example, see “A Look at Stored Data,” later in this chapter.

Notes

Note the following points:

-

Never redefine or delete storage for a class that has stored data. If you do so, you will have to recreate the storage manually, because the new default storage created when you next compile the class might not match the required storage for the class.

-

During development, you may want to reset the storage definition for a class. You can do this if you also delete the data and later reload or regenerate it.

For details, see “Useful Skills to Learn,” later in this book.

-

By default, as you add and remove properties during development, the system automatically updates the storage definition, via a process known as schema evolution.

The exception is if you use a non-default storage class for the <Type> element. The default is %Library.CacheStorageOpens in a new tab; if you do not use this storage class, Caché does not update the storage definition. The other common option is %Library.CacheSQLStorageOpens in a new tab, which is used primarily to support applications written before Caché provided classes.

Options for Creating Persistent Classes and Tables

To create a persistent class and its corresponding SQL table, you can do any of the following:

-

Use Studio to define a class based on %PersistentOpens in a new tab. When you compile the class, the system creates the table.

-

In the Management Portal, you can use the Data Migration Wizard, which reads an external table, prompts you for some details, generates a class based on %PersistentOpens in a new tab, and then loads records into the corresponding SQL table.

You can run the wizard again later to load more records, without redefining the class.

-

In the Management Portal, you can use the Link Table Wizard, which reads an external table, prompts you for some details, and generates a class that is linked to the external table. The class retrieves data at runtime from the external table.

This is a special case and is not discussed further in this book.

-

In the Management Portal, you can use the FileMan Wizard, which reads FileMan files and creates classes.

-

In Caché SQL, use CREATE TABLE or other DDL statements. This also creates a class.

-

In the Terminal (or in code), use the CSVTOCLASS() method of %SQL.Util.ProceduresOpens in a new tab. For details, see the Class Reference for %SQL.Util.ProceduresOpens in a new tab.

Accessing Data

To access, modify, and delete data associated with a persistent class, your code can do any or all of the following:

-

Open instances of persistent classes, modify them, and save them.

-

Delete instances of persistent classes.

-

Use embedded SQL.

-

Use dynamic SQL (the SQL statement and result set interfaces).

-

Use low-level commands and functions for direct global access. Note that this technique is not recommended except for retrieving stored values, because it bypasses the logic defined by the object and SQL interfaces.

Caché SQL is suitable in situations like the following:

-

You do not initially know the IDs of the instances to open but will instead select an instance or instances based on input criteria.

-

You want to perform a bulk load or make bulk changes.

-

You want to view data but not open object instances.

(Note, however, that when you use object access, you can control the degree of concurrency locking. If you know that you do not intend to change the data, you can use minimal concurrency locking.)

-

You are fluent in SQL.

Object access is suitable in situations like the following:

-

You are creating a new object.

-

You know the ID of the instance to open.

-

You find it more intuitive to set values of properties than to use SQL.

A Look at Stored Data

This section demonstrates that for any persistent object, the same values are visible via object access, SQL access, and direct global access.

In Studio, if we view the Sample.PersonOpens in a new tab class, we see the following property definitions:

/// Person's name.

Property Name As %String(POPSPEC = "Name()") [ Required ];

...

/// Person's age.<br>

/// This is a calculated field whose value is derived from <property>DOB</property>.

Property Age As %Integer [ details removed for this example ];

/// Person's Date of Birth.

Property DOB As %Date(POPSPEC = "Date()");

In the Terminal, we can open a stored object and write its property values:

SAMPLES>set person=##class(Sample.Person).%OpenId(1)

SAMPLES>w person.Name

Newton,Dave R.

SAMPLES>w person.Age

14

SAMPLES>w person.DOB

58153

Note that here we see the literal, stored value of the DOB property. We could instead call a method to return the display value of this property:

SAMPLES>write person.DOBLogicalToDisplay(person.DOB)

03/20/2000

In the Management Portal, we can browse the stored data for this class, which looks as follows:

Notice that in this case, we see the display value for the DOB property. (In the Portal, there is another option to execute queries, and with that option you can control whether to use logical or display mode for the results.)

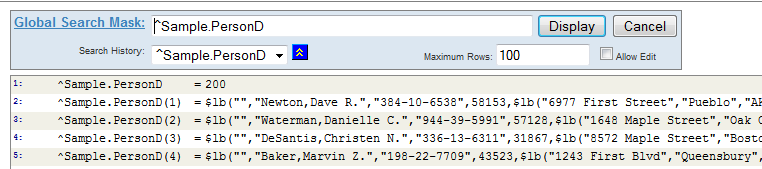

In the Portal, we can also browse the global that contains the data for this class:

Or, in the Terminal, we can write the value of the global node that contains this instance:

zw ^Sample.PersonD("1")

^Sample.PersonD(1)=$lb("","Newton,Dave R.","384-10-6538",58153,$lb("6977 First Street","Pueblo","AK",63163),

$lb("9984 Second Blvd","Washington","MN",42829),"",$lb("Red"))

For reasons of space, the last example contains an added line break.

Storage of Generated Code for Caché SQL

For Caché SQL (except when used as embedded SQL), the system generates reusable code to access the data.

When you first execute an SQL statement, Caché optimizes the query and generates and stores code that retrieves the data. It stores the code in the query cache, along with the optimized query text. Note that this cache is a cache of code, not of data.

Later when you execute an SQL statement, Caché optimizes it and then compares the text of that query to the items in the query cache. If Caché finds a stored query that matches the given one (apart from minor differences such as whitespace), it uses the code stored for that query.

You can view the query cache and delete any items in it.

For More Information

For more information on the topics covered in this chapter, see the following:

-

“Useful Skills to Learn,” later in this book, has information on viewing data and the query cache.

-

Using Caché Objects describes how to define classes and class members in Caché.

-

Caché Class Definition Reference provides reference information for the compiler keywords that you use in class definitions.

-

Using Caché SQL describes how to use Caché SQL and where you can use it.

-

Caché SQL Reference provides reference information on Caché SQL.

-

Using Caché Globals provides details on how Caché stores persistent objects in globals.

-

The InterSystems Class Reference, which is introduced later in “InterSystems Class Reference,” has information on all non-internal classes provided by Caché.